Rapid Recycle

by David Bacisin, published , last updated

Imagine a café with zero landfill waste: all food scraps are composted,

plates and cups are reused or recycled—unfortunately, this is not

Case Western Reserve University’s

BRB Café. While the

pre-consumer food waste decomposes at local farms, not a single recycling bin

is available within the café for customers to take part in preserving the

environment. How might we help Bon Appétit Management Company fulfill their

mission of providing food service for a sustainable future

by

implementing a few changes at the BRB Café?

Food services for a sustainable future.Neither recycling nor composting bin is within sight.

Research

Composting would provide one of the most environmentally-friendly solutions. We interviewed Erin Kollar, Recycling Director of the university’s Office for Sustainability, to get a sense of the waste management infrastructure in the region.

The primary consumers of compost are farms: to be useful as fertilizer, however, they need the right balance of vegetable and fruit scraps versus paper and meat waste. Kitchen waste often provides the desired balance, and the university has had success sending such pre-consumer waste to local farms. On the other hand, post-consumer waste contains too many napkins, paper plates, and contaminants, like plastic forks. While handling such a mix is possible, industrial composting in northeast Ohio is still too nascent to support the scale of a university, and equipment such as anaerobic digesters are well outside of the available budget for a privately-run operation.1

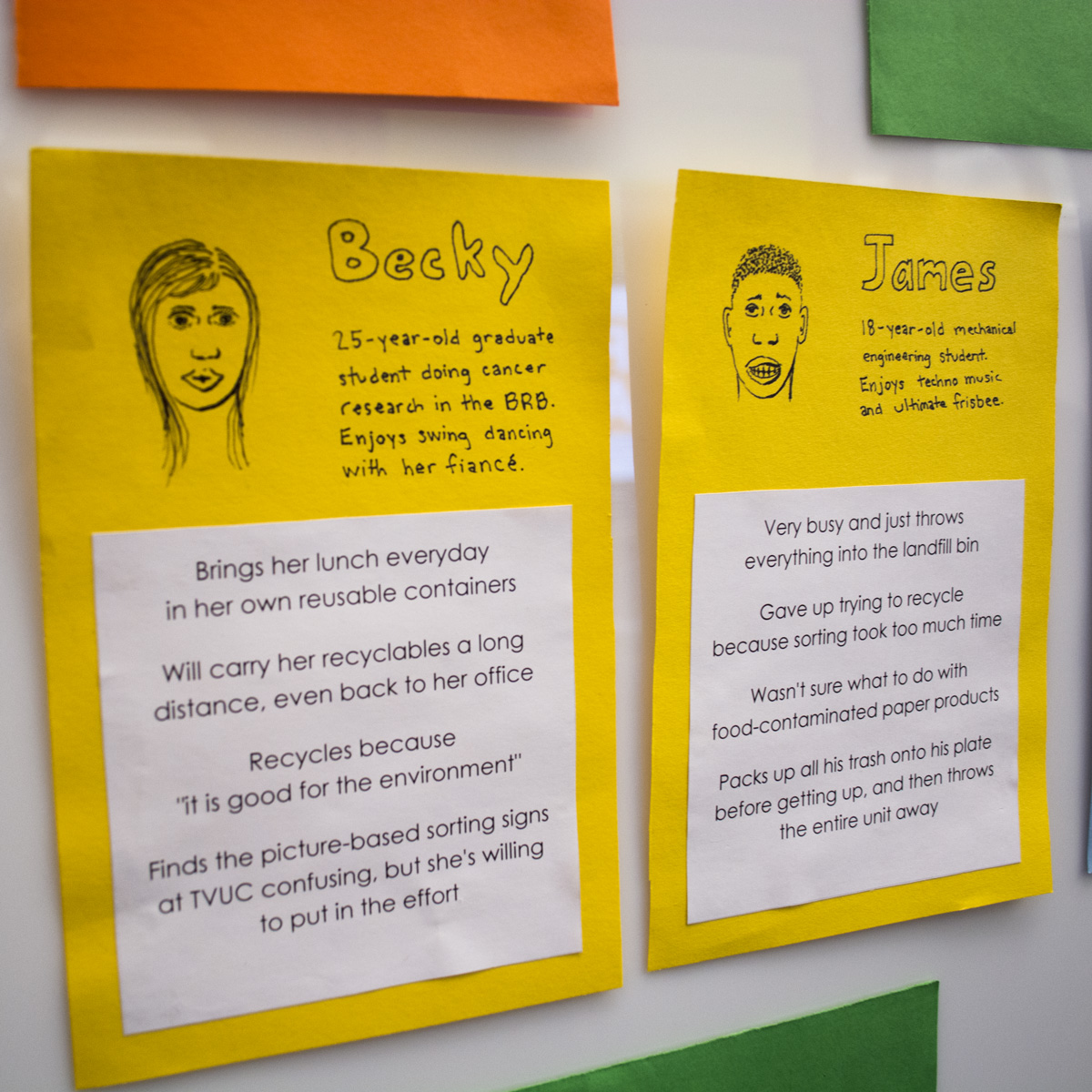

To better understand post-consumer waste, we conducted observations and

on-the-spot interviews of customers at both the BRB Café and another campus

cafeteria, the Tinkham Veale University Center (TVUC) food court. We found that

many people value recycling and sustainability, and though some will carry

their recyclables long distances to find an appropriate bin, others

simply don’t—or won’t—take the time. In the TVUC café, many

complained about the complexity of the bin signs, which featured 10 to 20 tiny images

showing what to place in which bins: we often heard comments such as,

[The signs] make it too hard, and don’t actually match what they serve

here.

We experimented with placement of open-top versus push-door landfill bins to see if a push door might act as a deterrent, which in turn might encourage people to use an open-top recycling bin. Our observations were inconclusive: while people tended to favor the open-top, many walked past the conviently placed bin to use the push-door. Whatever our solution might be, we would have to carefully consider how our target audience would physically interact with it.

The next step to really understanding waste involved getting dirty: we asked the café staff to set aside all trash for one day. That evening, we opened the bags and sorted the contents, weighing the amounts of plastic, metal, glass, compost, and landfill material. Though much of the waste was compostable, its paper-heavy composition meant it lacked the nutrients that farmers require. We discussed our options with the Office for Sustainability and ultimately decided to focus on the 33% of the waste (by volume) that was recyclable—but all of which was currently being sent to the landfill.

Insights

Seeking potential solutions, I derived three key insights from our many days of research:

1. Encourage sorting

During lunch hour, 77% of people packed up their trash onto a plate or into a box and then dumped the entire unit in a landfill bin. We needed to prevent them from packing up.

2. Make it faster and easier

While a couple dedicated customers spent upwards of 10 awkward seconds trying to sort their waste according to small pictures on the bin signs, most took an average of 3.8 seconds.

3. Improve knowledge of recycling

Many asked what can and can’t be recycled: what number plastics? If it has food residue on it, can it still be recycled?

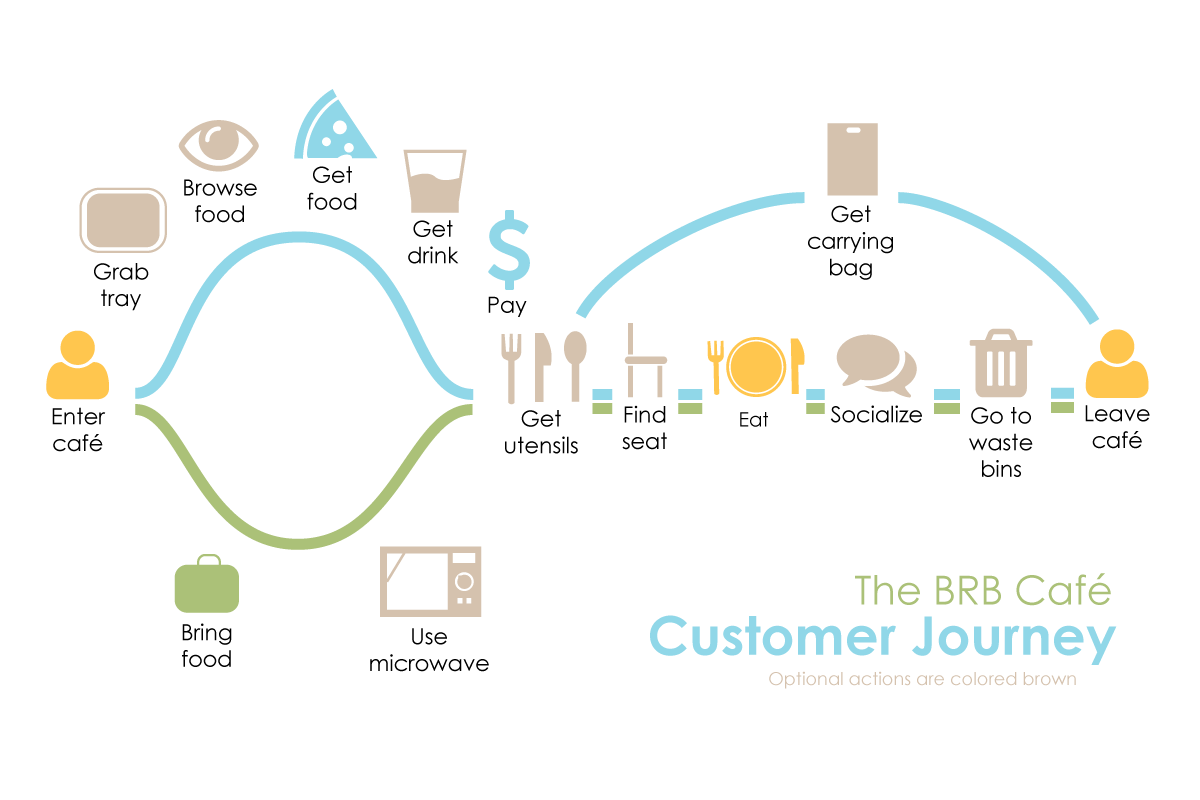

We needed to put people in a recycling mindset as early as possible, so I created a journey map to help us understand customer pathways. From this, we identified the many touchpoints where our solution could interact with the user.

Solution

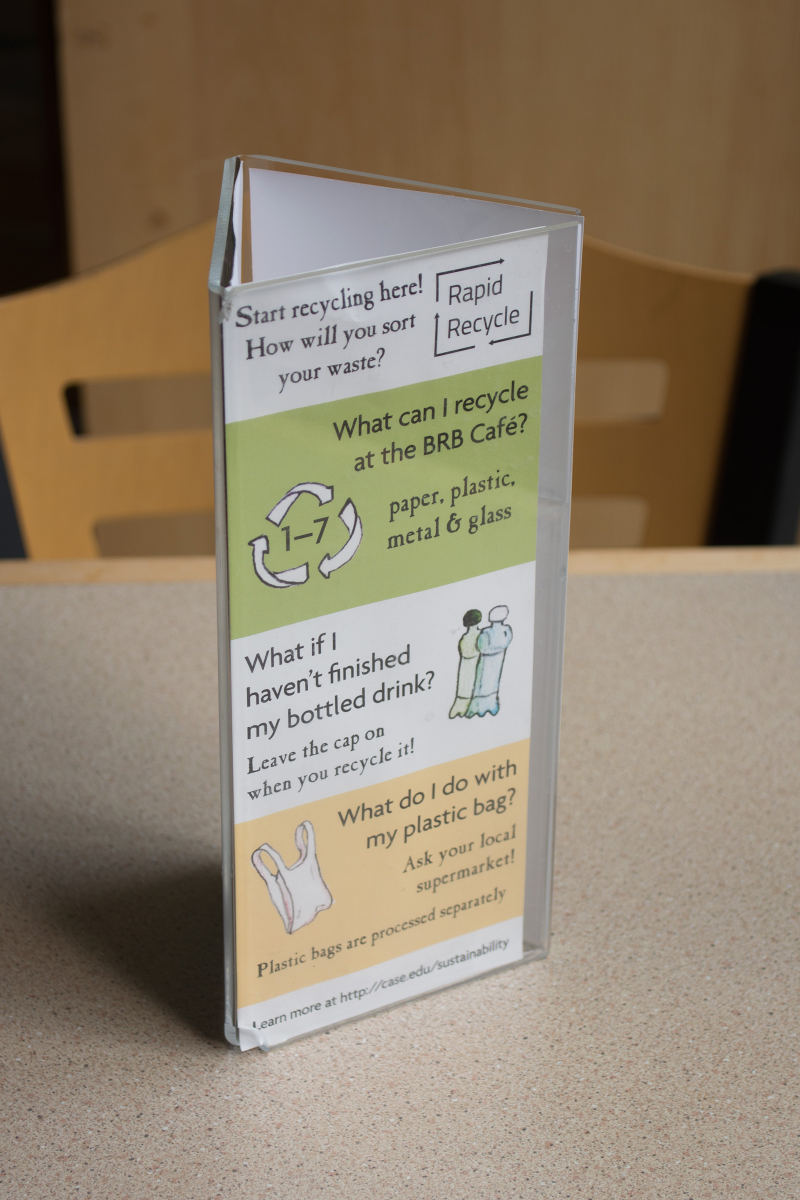

After many rounds of brainstorming and feedback sessions, we developed a system that both informs people about recycling and tries to speed up the process. Its name, Rapid Recycle, illustrates that recycling can be a fast and painless process—unlike what we saw in our research.

Testing

We based our success metrics on two dimensions: customer knowledge and actual behavior. Before installing any signage, we asked 42 customers which of eight items from the café they thought were recyclable: on average, they were 66% correct. With most being wrong about cups and utensils, we made certain to explain those two types of items on the table tents. From our waste sort, we knew that about a third of the waste was recyclable. For the post-implementation waste sort, we hoped to see all of the recyclables properly diverted from the landfill, and our focus would be on the contamination rate: how much landfill material ends up in the recycling bin, and how many recyclables still end up in the landfill?

While we have not had the opportunity to follow up with the Rapid Recycle system, we greatly appreciate the willingness of Bon Appétit and the Office for Sustainability to work with three persistent students over the course of two years.2 3

Footnotes

-

Kollar, Erin (Recycling Director of the CWRU Office for Sustainability). Personal interview by David Bacisin. Cleveland, November 7, 2014. ↩

-

For more information about sustainability at Case Western Reserve University, visit their sustainability site. ↩

-

All images on this page were taken or created by David Bacisin, © 2018 ↩